The single-lane gravel drive through the line of trees gave a shady respite to the heat of the June day. We snaked the car up the hill. According to the ochre-colored map, we had turned off old US 40 in the right place, but there wasn’t a tombstone in sight. In fact, as our tires crunched on, I held my breath. Were we trespassing, heading toward someone’s garage? Or orchard? Would the landowner come bursting out of the house waving a shotgun?

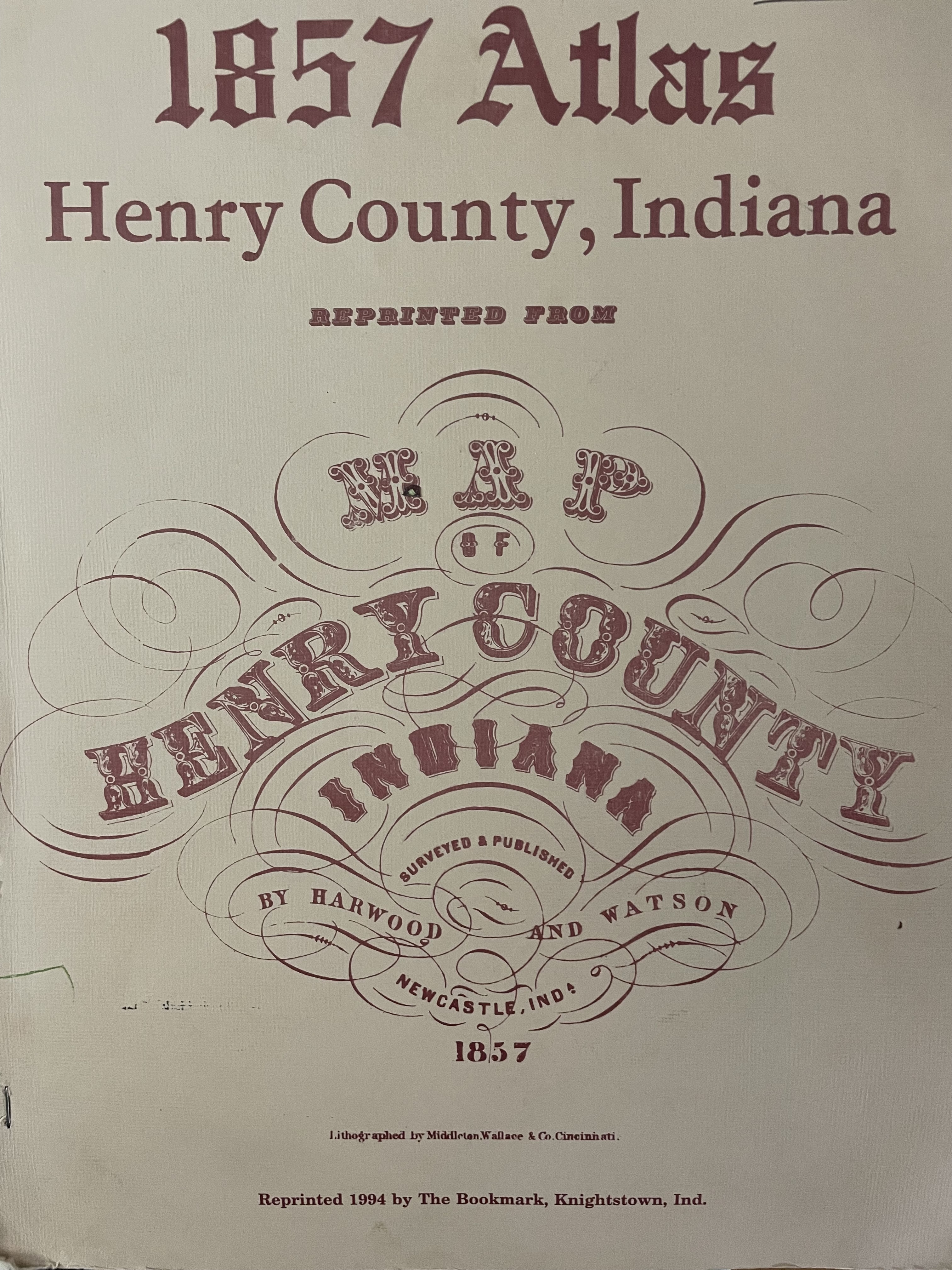

Using the 1857 Henry County Atlas, my son Ted and I hoped to find the old Raysville Friends Cemetery where our ancestor diarist Mary Jane Edwards was buried. We knew the middle of the story, the one Mary Jane had chronicled so well during 1866 in the diary she was given by her teacher colleagues in Jackson, Mississippi. And sadly, we knew when her journey ended, only four years after she had gone south to teach freedmen with her sister Lizzie. But we didn’t know where Mary Jane’s story ended. Could we find the place where she was laid to rest over one hundred years ago?

We’d been told it was east of Raysville, and that was only about an hour from home. But it was south of us, in a direction we traveled less frequently, and the landscape had changed considerably since Mary Jane’s day.

There was no longer an Indiana Central Railroad as we saw on the plat map. No depot. No mill. Even the National Road, US 40, had changed its route. And the current Raysville Friends Meetinghouse was much too new to have been the one Mary Jane attended.

But the plat map of Raysville did indicate a Friends MH (meetinghouse), much farther east— out of town, really. And it listed “SH” nearby, surely a schoolhouse. Was there a cemetery, too? There was no road heading north from the old highway. I drove slowly and hoped no one was behind me. With Ted’s help, I spotted a gravel lane. Could this be it?

Suddenly, as we inched to the top of the hill, the sturdy three-rail plastic fence came into view. Ultra modern and gleaming white, it separated a grassy space for two cars to park from our goal: the old cemetery.

I put the car in park, turned it off, and tentatively got out. I swatted away the gnats, as I looked about, still expecting a shout from an angry resident. Seeing no one around, I walked closer to the fence. There was a gate that securely latched, but it wasn’t locked. I lifted it and we walked in.

“Now how can we possibly find her grave?” I moaned. “Are we gonna have to look at all these tombstones?”

Luckily, Ted knew much more about online historical research than I did. He opened Find-a Grave and typed in Mary’s name. An image of her gravestone popped up.

We wandered down the hill to our right, but I didn’t recognize any names from Mary’s diary. So we strolled back up the hill to check the other side of the burial grounds.

In just a few minutes, Ted called out, “I think it might be over here. Here’s her mother.”

Sure enough, a three-foot proud obelisk bore Elizabeth Edwards’ name. Several feet away was a matching marker for her husband William, who had died nearly thirty years before her.

As we walked along the row of weathered limestone markers, I saw a smaller one with an unusual symbol on it. I leaned closer and saw the clear outline of a shield. The name was one I recognized: Nathaniel Parker, the hired hand on Mary Jane’s family farm.

“Oh, there’s a shield, Ted. Nathaniel must’ve served during the war.” I added a note to my growing list of questions. Was he drafted or did he enlist, a rarity for a Quaker?

“Yep,” he said, reading from Find-a-Grave. “It says he died in a fall from a roof.”

I paused for a moment. How ironic to escape death during the Civil War only to die from a fall.

“He left five little kids and his wife,” Ted read on.

I added more questions to my list. Who were his children? What happened to them? In the diary, he was very distressed about a neighbor girl who married someone else. Who did he end up marrying?

And then Ted called out, “Here it is.”

A few steps away, he’d found Mary Jane’s marker, nearly all encroached by moss or whatever darkens limestone over the years. Her name was carved into a banner at the top of keyhole shaped stone. Simple. Unassuming. Like I imagined Mary herself must’ve been.

I felt a pang of sadness. After reading and transcribing her diary with my mom over several years, Mary Jane had become more like a favorite character in a novel than a real person. But no, she really did live. And die… too young. At age 38.

We snapped a few pictures and then quietly headed back to the car with more questions. More thoughts. Enough to keep us wondering and researching for several months as we put Mary Jane Edwards’s daily record of 1866 into context.

Today, many writers work in secluded offices or cozy nests at home that they’ve created for inspiration. I have one, a former bedroom from one of our five kids. It’s packed with bookcases and a one-ton walnut three-drawer file and all kinds of art supplies. And in my comfy space with the wide availability of so many documents and information on the Internet, primary and secondary research is merely a couple of clicks away.

Even so, there’s something quite satisfying, even emotional, about doing physical research, with sandals and eyes on the ground.

It makes history -and historical people- seem more alive.

Leave a comment