Suffering from too much noise these days? Hip hop and rap versions of Christmas standards deafening you in all the department stores? Children incessantly whining and driving you nuts for this year’s must-have, the Tikduck Flying Orb Ball? Or lists of baking and shopping and decorating tasks rattling inside your head?

Maybe we need a silence break.

I’m a latecomer to the Thomas Merton Appreciation Society. But his work is the perfect prescription for the stress of the holiday season.

It’s surprising with my Quaker heritage and the silence in my religious upbringing that I’ve just now discovered Merton. You’d think with all that unprogrammed worship time and silent prayer, I’d have investigated the work of this modern-era contemplative long before last summer.

But I hadn’t.

I’d heard Merton’s name mentioned in a few sermons over the past thirty years. Even at religious writing and spiritual events, he was frequently quoted, but for some reason, his work hadn’t called my name.

That is until I attended my second silent retreat at Prairiewoods Franciscan Retreat Center in Iowa last summer. Spending a week in silence is a challenge. Whether it’s staying silently polite while opening doors and passing others in hallways or trying to contain a vocal reaction from something surprising you’ve created or seen while on a nature walk. Silence is a challenge and a blessing.

Retreatants’ time is usually filled with contemplation, prayer and meditation, and reading, indoors or out. Prairiewoods is enveloped by 72 acres of private forest and open grassland. In July, the wildflowers bloom tall and the grasses dance wildly in the prairie winds. Numerous outdoor spaces speak to participants even in the restorative silence.

Silent retreats are somewhat monastic in nature, and not for the timid. I can’t count the times I was teased about my probable lack of stamina for silence before I made it through my first week-long retreat. Especially because I first attended with my sister and later with friends.

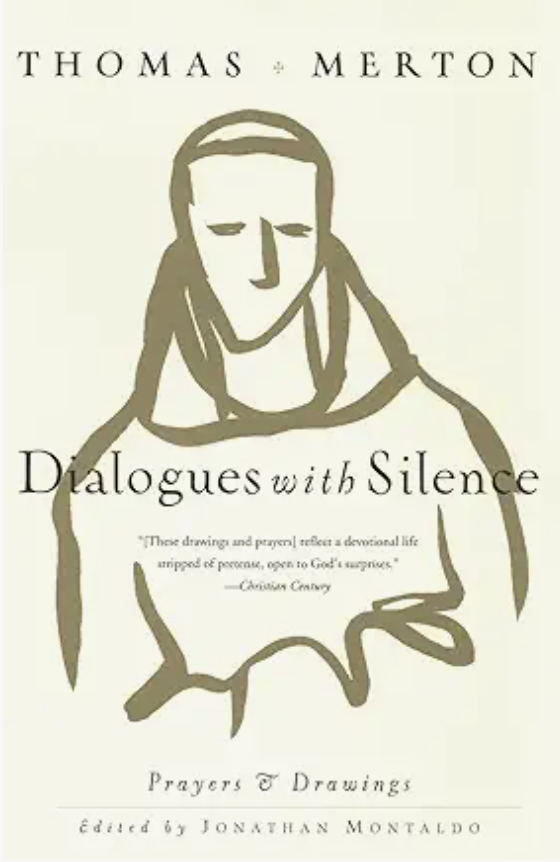

Thankfully, Prairiewoods also has an immense library categorized by subjects. The ample reading material made filling the silence easier for many of us novices, and because the center is non-sectarian, finding books about such diverse topics as the enneagram, labyrinths, and Buddhism, made inspiration easy. Even with all the hefty competition, Thomas Merton’s Dialogues with Silence shouted at me.

As an introduction to Merton, Dialogues was fascinating. Editor Jonathan Montaldo pared and paired Merton’s creation of over 800 line drawings with his 400-plus prayers to fashion a collection of conversations and supplications to God that will inspire and induce readers to follow their unique journeys.

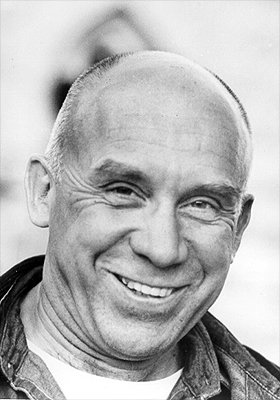

In the preface, Montaldo describes Merton as having “ a critical mind and a poet’s passion” (x). Surprisingly, he relates that Merton “wantonly loved books women, ideas, art, jazz, hard drink, cigarettes, augment, and having his opinions heard” (x). Certainly, not characteristics generally associated with a monastic calling! Nonetheless, at 23, Merton became Catholic, and three years later, to the dismay of his friends, he committed to the isolated life of a Trappist monk (x).

Merton’s appeal to readers since his first book was published in 1944 surely has been his brutal honesty about his attempts to be a better servant of God and his admissions of falling short.

On page 53 of Dialogues, I read, “Save me from my private, poisonous urge to change everything, to act without reason, to move for movement’s sake, to unsettle everything you have ordained” (53).

Who of us during the holiday season cannot relate to a feeling of chaos in our lives and being out of control? When we allow social media, advertising, and cultural movements to pressure us with the newest trends to make our holiday adventures and celebrations perfect, we often forget the origins of the season.

Merton follows his lament with a request that’s perfect for our hectic, frenzied moments: “Let me rest in Your will and be silent. Then the light of Your joy will warm my life. Its fire will burn in my heart and shine for your glory. This is what I live for. Amen, amen” (53).

Silence: restorative, joyful, and transforming.

During the retreat, I ordered Dialogues on Amazon. Once home, after dog-earing and highlighting a dozen or so pages with images or words that spoke to my condition, I needed to know more about this mid-century modern mystic. I was first in line on Libby to borrow The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton’s million-copy-selling autobiography.

In it, I learned that Merton was born to a Quaker mother and a mostly absentee artist father. After his mother died when Merton was six, he was shipped off to a French boarding school and later lived in England and the US. Despite his unstable childhood, Merton managed to graduate from Columbia University. There, he met a Hindu monk who steered him back toward his Christian faith. As he worked on his Ph.D. at Columbia, Merton felt the call to the simple and silent monastic life of the Trappists. In 1941, he joined the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Trappist, Kentucky.

Merton kept many journals and worried that his writing interfered with his silent monastic calling. Nonetheless, he was able to publish his work through friends he had met at Columbia and with the support of his religious superiors. He soon veered into peace studies linking Eastern and Western religious traditions. Eventually, many of his 60-plus works were translated into 15 languages, largely because he had the support of the abbot where he lived. Sadly, his provocative positions for the era made his poetry and activism anathema to some elements of the Catholic upper echelon. Indeed, some followers believe his untimely death at a religious conference in Thailand was never suitably explained.

Merton’s life and writing about silence and listening speak to me. Especially during this “most wonderful time of the year,” I feel the need for quiet contemplation. Unfortunately, as I spend more time indoors and creating festive holiday spaces and events for family and friends, finding quiet can be a challenge.

In Dialogues, Merton is quoted, “I listen to the clock tick. Downstairs the thermostat has just stopped humming. God is in this room. He is in my heart. So much so that it is difficult to read or write” (63).

If only it were just a clock and furnace I heard.

Today, our noise might just as easily be hearing Christmas movies blaring on the television, noises from too many delivery vehicles outside the window, or kids wound up after consuming too much sugar.

Finding peace and hearing God’s voice amidst the holiday noise is a challenge, but it’s one that spending time with Thomas Merton’s work can help us all achieve.