It was nothing remarkable that I did. Nothing that I especially deserved. It just happened.

That’s how my 3xs great aunt’s diary has become a novel.

Over fifteen years ago, while visiting my parents one Sunday afternoon, I suddenly remembered that my mom had an old diary from her dad’s family that I’d heard about from time to time. I’d never known much about it, just the basics. Her great-grandmother Lizzie had gone to Mississippi to teach freed slaves. Mom had a gold ring passed down from Lizzie, too. It had an inscription from her students inside the dark gold band. I’d never even seen the diary, and I’d only seen the ring once when I was a teenager.

So what made me think of it at that moment? I have no idea. Maybe I had reached the Civil War unit in my American literature classes and suddenly thought about it. Maybe my mom had gotten a new ring, or maybe she was cleaning out some genealogy files and mentioned it. I don’t remember.

But I asked her to see the diary that afternoon.

And so our project began.

Mom disappeared to dig into some mysterious closet at the back of the house and then returned to the living room triumphantly. She handed me a tiny dark brown leather book, no more than 5 inches tall by 6 inches wide when fully opened.

Inside the front cover, I read the inscription in a backhanded script with flourishes on the capital letters, like from a fountain pen :

“Token of our regard”

Jno and E. T. Watson

Jackson Miss

1866

I turned the delicate ecru pages past the informational section with its postage rates, list of eclipses, and phases of the moon for each month, to see a six-page list of “Memorable Events in the Secession Rebellion, Together with the Fluctuations in Gold,” all printed in faded black and red ink. I read aloud the section titles.

“Clearly, this was purchased down South,” I mused.

On the following page, below a meandering tangle of vines and leaves encircling “1866 “was the header in an italicized font: “Monday, January 1.”

And below, written in a perfectly slanted and delicate faded brown ink, began the record of my ancestor who had gone to Mississippi to teach the newly freed slaves.

I flipped through the pages: most all were filled to the margins. A few pages threatened to escape the thread that bound the petite book together. That shouldn’t have been a surprise. I was holding a book that had been in our family for almost 150 years!

I couldn’t read all of the spidery script; its ink was faded and the words were squeezed onto the compact, lined page. But I was intrigued. What did this teacher have to say about her assignment? What happened that was notable enough to record in this pocket-sized journal?

Even I with years of deciphering student handwriting and my own practically illegible script stumbled through the first page as I read aloud:

This morning ushered in the new year. A glad and joyous day it has been to thousands who have celebrated it with feasting and merriment. Around the bier of the dying year, few mourners were gathered, but many listened closely for the knell of the departing year, that they might join in the shout of the New Year. A happy new year to all the world over, may it really be and may all drink more deeply of the water of life, may all learn wisdom that their joy may be a deep pure joy, which the world cannot give, neither take away; and may they turn to Him who is able to help when disappointment comes, clouds overspread the sky.

Mom and I exchanged looks of dismay. Such lofty sentiments! Would it all be written in this soaring register? Maybe that was why no one in the family had transcribed it before now.

I turned the page and haltingly read on:

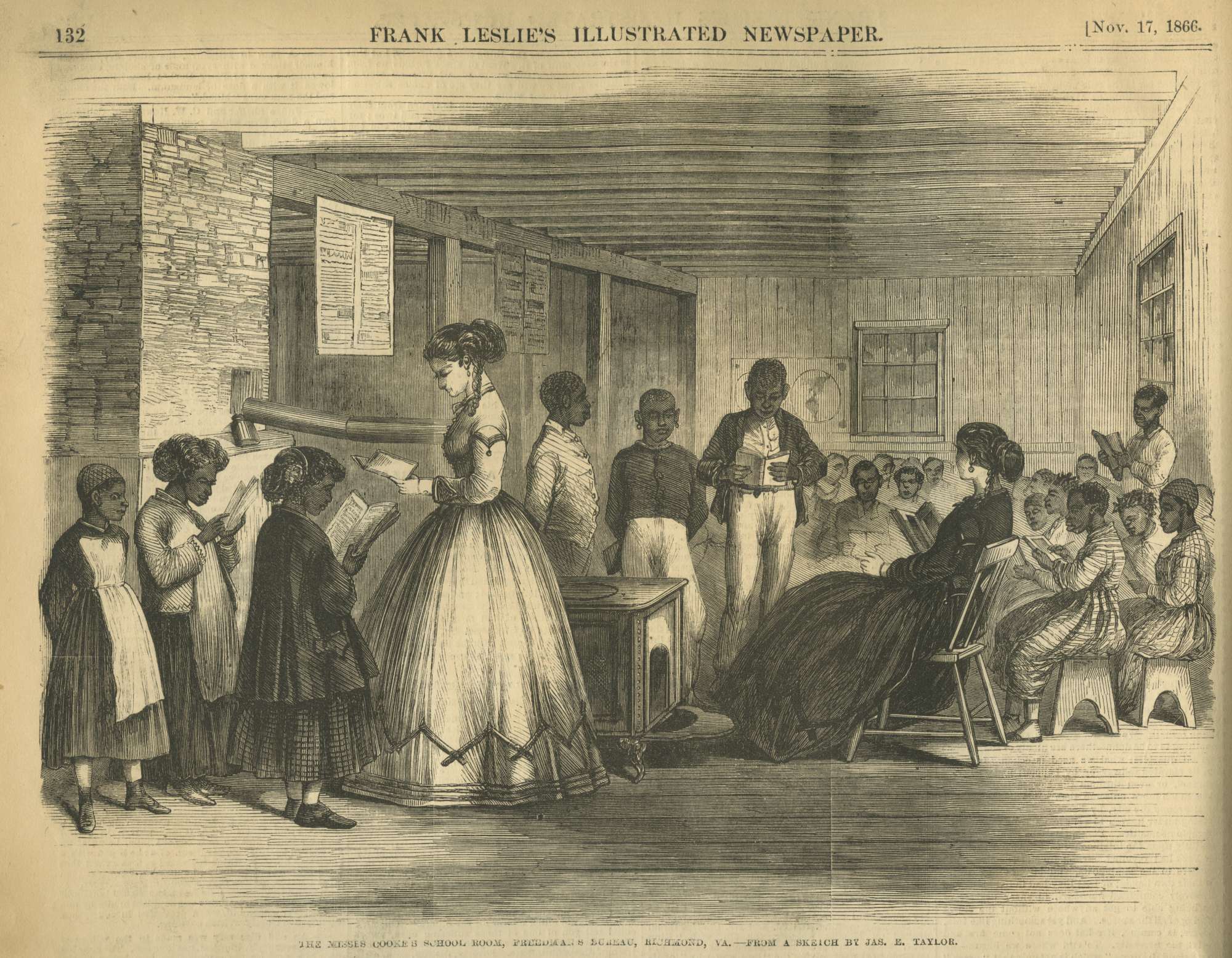

Today [I] opened school for the first time in the new schoolhouse designed for me, with about 45 scholars of both sexes, and ages from 6 years to 25, most of them in the very first principles of education. A very small number, if any of them are of pure African descent and many of them show that they have a large proportion of white blood in their veins.

Education has been withheld for this people as faithfully as if it was poison, by those presumed to rule over them, but the days of their cruel reign are past and the oppressed, now free, may go forth, in the enjoyment of privileges hitherto denied them.

“Wow,” I gasped. “I wonder what happened to her… and to her students.”

Lofty words and all, Mom and I were hooked! We had to know more!

That afternoon, we vowed to puzzle out the daily account of this teacher of freedmen, our ancestor. Mom scurried to the den for a magnifying glass and came back to the living room to settle beneath a bright lamp. She promised to begin typing a transcript of the diary that very night.

She did.

And so we began our vicarious adventure teaching freedmen during Reconstruction by transcribing a family diary.

.

Leave a comment